Agnese Dolci, in the Workshop of her Father

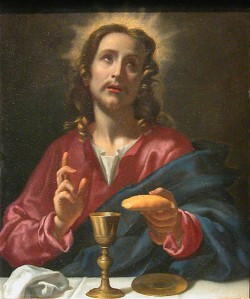

One of the paintings I was looking at this week in The Louvre: All the Paintings, Christ Blessing, also known as The Institution of the Eucharist (ca. 1656), was attributed to the workshop of Carlo Dolci (1616-1686). I have come across references to artists’ workshops before when learning about Louvre painters, usually with respect to artists in training who are employed in another painter’s workshop, but very occasionally in the attribution of a painting: two of the Louvre’s works by Veronese (1528-1588), for example, are characterized this way and another as by Veronese and workshop, an interesting, subtle distinction; likewise, two of the Louvre’s works by Bassano (1549-1592) are “workshop of”, with a third labeled “follower of Bassano”. But Dolci’s workshop holds a special interest because it brought me very close for the first time to an attribution of a painting to a woman artist.

But only very close. I was excited for a while. The Catholic Encyclopedia article on Carlo Dolci by Leigh Harrison Hunt states, “Agnese Dolci, who died the same year as her father, not only made marvellous copies of the master’s pictures, but was herself an excellent painter. Her ‘Consecration of the Bread and Wine’ is in the Louvre.” In the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, a painting called The Consecration housed at the Louvre is listed as a work by Agnese Dolci. But the Grove Dictionary of Art, the reference I have been relying on, does not treat any painting in the Louvre as the work of Agnese, saying instead of her that “no securely autographed painting is yet known, although a supposedly signed Self-portrait is known from photographs (Florence, Fond. Longhi). A Christ and the Samaritan Woman with St Teresa was auctioned in Florence in 1984; Dolci’s autograph study for the figure of Christ is in the Louvre, Paris, but the finished painting clearly includes the work of other hands.” Thus, the Grove Dictionary account agrees with the Louvre’s attribution of the painting of Christ to the workshop of Carlo Dolci, and not to Agnese in particular.

Although it is rather a non-story, I’ve gone ahead with writing about Agnese; there is clearly almost a story here about all the daughters and wives and other aspiring female painters to whom we are indebted for art that has reached us only under the signatures of their male masters and for whom we should mourn because of the paintings they might have done.

Did Agnese consider herself fortunate, I wonder, to have a father who would teach her and then allow her a place in his workshop, or was she frustrated that her talent was not acknowledged as uniquely her own? In blog post 5, I wrote that the early life of St. Louis of Toulouse, when he was sent to Spain as a hostage to gain the release of his noble father, would be a great subject for a novel. I feel the same way about Agnese.

For the present, at least, I appear to be alone in finding such potential in Agnese, but a quick check confirmed that I was definitely not the first to find the theme of early women painters a likely fiction subject. Another painter’s daughter, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653), whose career overlaps Agnese’s to some extent, was the subject of a novel by Susan Vreeland, The Passion of Artemisia, in 2002. On her website, Vreeland characterizes Artemisia as “the first woman to paint large scale historical and religious paintings, the first woman to be admitted into the Accademia dell’ Arte del Disegno in Florence, the first woman to make her living by her brush, the only female artist to adopt Caravaggism, and most significantly, one of the greatest artists of the Italian Baroque (17th century).” Artemisia’s father, Orazio (1562-1639), has two paintings in the Louvre’s collection, Rest on the Flight into Egypt and Public Happiness Triumphs Over Danger. Vreeland’s website includes the interesting story of her first encounter with Artemisia’s work: http://www.svreeland.com/gen-art.html.

The little I’ve read to date about Carlo Dolci suggests that Agnese probably had a difficult life, especially if she loved her father. He planned laboriously and painted very slowly, which meant that he was rarely chosen for large-scale church fresco projects. The speed with which his contemporary Luca Giordano (1634-1705) worked is said to have caused Dolci to fall into a depression from which he never recovered. At the same time, the Dolci workshop was a busy place, particularly in making copies of his works, a project that Dolci shared with his pupils, including Agnese. Perhaps she was content with the task, since it was one that her father also engaged in as part of the painter’s craft.

The gender imbalance among artists is not repeated in the images the artists painted. Men did the painting, but many of their subjects were women, and, of course, the models they worked with to create paintings of women were women. Carlo Dolci is identified as the creator of two Louvre paintings; one depicts the Virgin Mary and the other a very feminine-looking angel of the Annunciation. The painting produced by his workshop, and therefore probably, at least in part, by Agnese, is an image of Christ. I’ve included it in this post.